1st Courthouse

Building Completion Date: 1876

County Seat: Breckenridge

Present Status: Gone

Building Materials/Description: Log cabin

2nd Courthouse

Building Completion Date: 1883

County Seat: Breckenridge

Present Status: Gone. Demolished 1927

Architect: James Edward Flanders

Architectural Style: Italianate

Building Materials/Description: Entry remains, stone reused in 1st Assembly of God church.

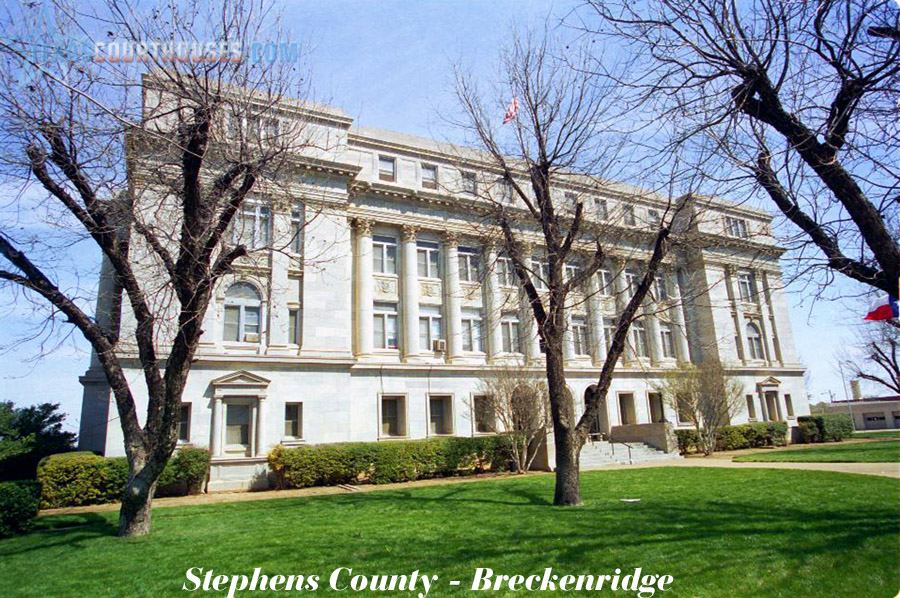

3rd Courthouse

Building Completion Date: 1926

County Seat: Breckenridge

Present Status: Existing. Active

Architect: David S. Castle

Architectural Style: Classical Revival

General Contractor: Walsh & Burney, San Antonio

Building Materials/Description: Constructed of Indiana limestone. $454,222.02

National Register Narrative

The Stephens County Courthouse, designed in 1925 with construction spanning through 1926, creates a dramatic governmental landmark for both Stephens County and the city of Breckenridge. The courthouse occupies the public square central to the town’s gridiron street system. Only a nearby former hotel rivals the building’s lofty four-story height for domination of these rolling, arid plains in north central Texas. The rectangular plan is quartered on the main floor by hallways crossing at the building’s center, accessing a public staircase in the north corridor. A full basement, slightly raised, and four upper floors encompass a variety of rooms accessed by extensions of the open staircase. Abilene architect David Castle finished this efficient composition in a sophisticated Classical Revival styling, rendered in light gray limestone throughout. The courthouse grounds feature the preserved south portal of the 1883 courthouse (a Contributing structure) and walks that augment the primary south facade and centered entry steps while directing pedestrians past several memorials and mature pecan trees to the east and west side identical entrances. The north facade and its central entrance are highly detailed, but now clearly read as the building’s rear because of pavement to accommodate automobiles on the block’s north side. Despite this landscape abuse, plus somewhat sensitive window replacements and minor interior alterations, the courthouse and grounds retain a full range of integrity that establishes National Register eligibility.

Stephens County was created in 1858 from the north central Texas plains and cross-timbers region. The county’s boundaries are roughly square, indifferent to geographic features and approximating a standard 19th century 30-by-30- mile political unit of 922 square miles. This semi-arid landscape is drained by the Clear Fork of the Brazos River, meandering along the north margin of the county. The area’s surface features, suitable for small-grains production and livestock grazing, cover bituminous coal strata and huge oil deposits of the Breckenridge Field. The town of Breckenridge, the county seat, sits about five miles west- northwest of the county center. The town’s gridiron street system is aligned with cardinal directions, centered on the public square that occupies high ground between two branches of Gonsolus Creek. The courthouse fronts on the main east- west thoroughfare of Walker Street/U.S. Highway 180, although the intersection one block east with north-south Breckenridge Avenue/U.S. 183 shifts the town’s circulation center to that major crossroads.

The present full-block public square, Block 8 in the town plat, was originally subdivided, and the county’s first permanent courthouse of 1883 occupied Lot 10 at the southeast corner. This Italianate-style building was designed by Dallas architect James Edward Flanders and constructed of local red sandstone by Rosenquest. Their building’s vertical-emphasis three-story walls featured dressed-stone first-floor quoins, window and door surrounds, and sill bands across each elevation. Quarry-faced stones, of reduced dimensions above the first floor, completed each elevation’s richly textured surfaces. A complex roof system was bordered by pressed-metal cornices and entry-bay gables, and accented by a figure of justice above the south entry plus a very tall central cupola. Construction of the 1926 courthouse immediately northwest on the balance of Block 8 apparently took place while the 1883 building remained in use. Upon demolition of the older building about 1927, its south entry portal of sandstone was retained in situ as a memorial. Other salvaged details from the razed courthouse are found reassembled in the form of a one-story basilica- plan church on Breckenridge Avenue.

Breckenridge and its commercial heart developed modestly through the early 20th century, and early businesses filled storefront lots around the courthouse square. With discovery of oil in 1916 under and around the town, followed by intensive local drilling after 1918 and arrival of two railroads in 1920, the business district experienced much new construction. Because of geography and prior development of the town center, both the Cisco & Northeastern Railway building north from a mainline connection at Cisco and the Wichita Falls, Ranger & Fort Worth Railroad building south from mainlines at Wichita Falls established their depots five and six blocks, respectively, east of the courthouse. While regional road connections south to Cisco and Eastland originally started from Rose Avenue just west of the courthouse, the first highway from Wichita Falls terminated more than one block to the east. These important rail and road orientations effectively shifted subsequent commercial development away from the public square. With 1920 construction of the substantial First National Bank building (now a museum) one block east near Walker and Breckenridge streets, then 1928 completion of the ten-story Burch Hotel (now a bank) at a corner of that intersection, the courthouse square evolved to a park-like presence respectfully adjacent to downtown.

The courthouse grounds occupy all of Block 8, acquired in balance for construction of the new building, and landscaped after its completion in 1926. Concrete walkways extend the cross-axes of the building’s interior hallways, leading into the south (main) entry from West Walker Street (paved in dense, red Thurber bricks), on the west side from North Rose Street and on the east side from North Court Street. Formal exterior stairways lead up from these walkways to each set of entry doors likewise into the north elevation from the main parking area for an effective pedestrian transition into the building, in classic Beaux- Arts design tradition. A lengthy disabled-access ramp of concrete has been poured over part of the east entry stairs. The block’s southwest corner is devoted to a grouping of commemorative markers, and its southeast corner features the 1883 courthouse entry portal and other historical markers. Mature (though recently radically pruned) pecan trees shade the west, south and east lawns of the block; crape myrtles and trimmed hedges outline the courthouse foundation on those elevations.

The 1926 Stephens County Courthouse footprint is rectangular with long axis running east-west. Its slightly raised basement, accessed by descending steps in the north stairway chase, as well as by an elevator immediately east of the chase, is divided into four areas: boiler room, supply room, county clerk records storage (with private stairs from the clerk’s office above), and large vault. Cross-axis hallways on the first floor are accessed and lit with sunlight through a grouping of three entry-door pairs on the south, double-door entries on the west and east ends, and two entry-door pairs into the stair chase on the north. Hallways feature terrazzo floors and marble wainscots highlighted by oak doors and trim, plus a number of bronze commemorative plaques in the south entry hall. The second floor, accessed by the main staircase that splits into two flights above its mezzanine, features a large open two-story district courtroom with balcony on its east end, and originally a similar courtroom on the west that is now partitioned into small offices and storage. The third floor is accessed by double stair flights and is now used primarily for storage. Jail functions occupy the entire fourth floor, divided into cells, recreation room, offices and a former sheriff’s apartment converted to storage.

Exterior design features of the courthouse reflect a high level of maturity in Beaux-Arts (pronounced bo-zar) styling, popular for American public buildings from the 1890’s through the 1930’s. This French-originated system of design methods-rational organization of the building spaces and their services within a formal public setting-and exterior ornament-heavily influenced by ancient Roman classicism in details discovered by archeologists near the Mediterranean Sea-reached an apex in the United States with 1920’s development of the Federal Triangle office complex in Washington, D.C. Such public buildings, alone and in groups, copied Greek and Roman temples in symbolic elevation of democracy as the basis of American culture. The specific bottom-to-top organization for each public building in the Federal Triangle-“base” for entry floor, “shaft” of columns creating window spaces for the majority of interior offices, and “attic” for a top floor above the entablature-directly influenced architect David Castle at Breckenridge.

Durable sculpted Indiana limestone, whose import the town’s railroad connections made possible, conveys these classical details on all four elevations. The building’s south facade is divided into three major bays, extending forward on the east and west, signifying the courtrooms inside these bays. The central bay carries a massive two- story row of 10 engaged Corinthian columns, whose capitals feature lone stars and eagles. These support a fully detailed entablature, with a frieze displaying the words:

JUSTICE, EQUITY AND PEACE ADMINISTERED ALIKE TO ALL PEOPLE.

The west elevation continues the horizontal extension of classical temple details, but its central bay of entry base and four full columns is extended out as a porch for the former courtroom inside. The east elevation exactly repeats the west side porch bay extension and details. The north elevation also continues the temple theme in reflection of the south side, but all “columns” here are reduced to shallow relief as pilasters.

Windows throughout the building were replaced in the 1980’s with unfinished aluminum frames, and at some recent time fabricated metal fire escapes were attached to the north elevation at the 1st through 3rd levels. Despite these alterations and minimal changes to the building’s surrounding landscape and interior, such as the disabled- access ramp and north courtroom partitioning, the 1926 Stephens County Courthouse retains integrity to a high degree in the aspects of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling and association.

The 1926 Stephens County Courthouse in Breckenridge, the third courthouse built in Stephens County, symbolizes the prosperity that developed in the town and county during the 1920’s oil boom. Designed by Abilene architect David S. Castle, the Classical Revival building also represents the dominant institutional building type associated with local government in Texas. For its role in Stephens County government during the past 70 years, the Stephens County Courthouse meets Criterion A in the area of Politics/Government at the local level of significance. As an excellent local example of the Classical Revival style in early 20th century public buildings, the Stephens County Courthouse also meets Criterion C in the area of Architecture at the local level of significance.

Anglo settlement began in the area now known as Stephens County during the late 1850’s when John R. Baylor built a cabin on the Clear Fork in 1857, in an area primarily occupied by Comanches and Tonkawas. Other settlers soon followed and just one year later, the Texas Legislature established Stephens County. Originally named Buchanan County after President James Buchanan, the county was renamed in 1861 after Alexander J. Stephens, vice president of the Confederate States of America, and the small town of Picketville became the temporary county seat. Ranching and other agricultural endeavors supported the small but growing population.

After the Civil War, thousands of new settlers moved in to the area during the 1870’s, warranting the construction of a courthouse. According to some, justice was first meted out under a huge oak tree at the northeast corner of the present courthouse square. The jurors and deputy sheriff slept in a nearby livery stable and prisoners were locked in a plank building at night while the sheriff slept outside. In 1872, E.L. Walker, the first county judge, was allowed the sum of $26.86 to buy lumber for a 22 x 40 foot pine building with desks lined around the walls for county officials. The building also served as a church, post office, dance hall, and as a meeting place for the community. In 1876, the county was reorganized with Picketville as the official seat of government and renamed after U.S. senator from Kentucky and vice president under Buchanan John C. Breckinridge, although the spelling of the name evolved to the current Breckenridge.

In 1877, the courthouse building received a 20-foot extension to accommodate growing needs. By 1880 the county population reached 4,725 and the arrival that year of the Texas and Pacific Railway across the southern tip of the county between Strawn and Ranger further spurred growth. County officials decided to build a new courthouse and levied taxes on all county property at the rate of 50 cents on each $100 worth of land and issued bonds to build a native stone courthouse not to exceed $30,000. The new three- story, red stone courthouse was completed in 1883. Over the next few years, Breckenridge quietly served as the government and trading center of the county.

By 1900, the population of Stephens County reached 6,466, with cotton and cattle as the leading agricultural commodities. By the 1910’s and 20’s, however, the number of farms in the county dropped by more than 50 percent, a combined result of the widespread drought of 1917 and 1918 and the discovery of oil on the W.L. Carey farm near Caddo in May 1916. Soon after, the drilling of more productive wells led to a terrific economic boom centered around Breckenridge in 1921. Over 200 wells were drilled within the city limits and in one year the Breckenridge oil field produced 15 percent of all oil in the U.S. and one third of the petroleum in Texas. The 1921 boom brought thousands of workers and speculators to the small town, raising the population from an estimated 1,500 in January 1920 to 30,000 by 1921. By July of that year, the Wichita Falls, Ranger and Fort Worth Railroad laid tracks through the town, joined later by the Cisco and Northeastern Railway.

This incredible growth led to the obvious need for a larger courthouse. An article in the March 24, 1924, issue of the Breckenridge Daily American states that the “present structure erected in 1883 is unsafe for records” and that “many citizens feel that (the courthouse) has filled well its purpose and the business of the county has outgrown its size and structure.” In June of that year, voters approved $500,000 in bonds to build a new courthouse and jail by a vote of 521 for and 119 against. In November, Mayor T.B. Ridgell began to circulate a petition calling for a smaller bond issue. In January 1925, the measure passed, this time approving $250,000 in bonds by a vote of 943 for and 915 against. Several taxpayers quickly contested this vote, claiming that non-property tax payers cast some of the votes and without these the measure would not have passed. At a meeting at the courthouse in July, County Judge John W. Hill proposed to move ahead without waiting on a court decision on the contest suit. When the public didn’t voice any opposition, he turned the matter over to the County Commissioners who proceeded with construction plans. An article in the July 17, 1925, Breckenridge Daily American stated that due to the “splendid financial condition of the county” over the past five years, “the big monument to the prosperity and pride of the county’s citizenship would go up immediately.”

Abilene architect David S. Castle, who designed Breckenridge’s 1922 Municipal Building and the 1924 Mitchell County Courthouse in Colorado City, designed the Stephens County Courthouse. Newspaper articles reported that the Commissioners Court visited several courthouses and jails in other cities including Ft. Worth, Amarillo, and El Paso to inspect plans. When they decided upon plans, the newspaper described the new courthouse as being “four stories high, with the jail on the top floor-in accord with the most modern methods of courthouse construction.” In October, contracts went to the firm of Walsh and Burney of San Antonio for an estimated construction cost of nearly $400,000. When the county ran out of money, Walsh and Burney terminated the contract and the county issued another $140,000 in warrants to renew the contract. The final cost of the new courthouse added up to $410,149.40, $26,873 more than the agreed sum.

When construction on the new courthouse finally began in 1926, the oil boom in Breckenridge reached its peak. The county spared little expense to create a building that the newly rich oil citizens felt they deserved. The 1883 courthouse was atypically located at the corner of the square, so the county purchased the lots and buildings on the west and north part of the block in order to build a courthouse that would occupy the center of the square. Newspaper reports stated that the old courthouse would be left standing until the completion of the new courthouse. When the 1883 courthouse was torn down, the front porch and sandstone entryway were retained as a monument on the southeast end of the block.

Although county offices didn’t move into the building until December 1926, dedication ceremonies were held on July 4 of that year. The high school band played patriotic music while American Legion members marched flags to a temporary platform. County Judge John W. Hill presented the building to the American Legion for dedication and former Abilene mayor and civic leader Dallas Scarbrough gave the dedication address. It is possible that Scarbrough’s influence may have played a role in the selection of an Abilene architect. The courthouse was dedicated to war veterans of Stephens County with a bronze tablet bearing the names of Stephens County veterans placed on the left wall by the south entrance.

The oil boom in Stephens County lasted only a few years, and although the city remained a center for commerce and oil production, the city’s population fell to 7,569 by 1930. The onset of the Great Depression through the 1930’s furthered this decline, and the courthouse bonds became an economic burden to the county. After refinancing, the debt wasn’t paid off until 1962, 36 years after completion of the building. County Auditor Earnest Maxwell had the last paid bond framed and hung on his wall as evidence of a long, hard financial pull for the county.

Over the 70 year history of the courthouse, certain incidents and trials stand out in the minds of local citizens. Former County Treasurer Pauline Morgan recalled a case where a man accused of killing his wife on the streets of Breckenridge resided three years in the county jail before being sent to the electric chair, spending most of those years barking like a dog out the barred windows to convince people of his insanity. Former County Judge Miller Tuttle remembers a trial where a preacher was charged with driving while intoxicated and during the testimony, spectators jammed every available space in the district court room, some bringing lunches so not to lose their seat. Former Deputy County Clerk Evelyn Cole recalls the day when a disgruntled loser shot and wounded attorney C.J. O’Connor in front of the courthouse. The most famous case, however, was the Pearl Choate case. Pearl, a practical nurse, brought her charges, a very old and wealthy couple, to Breckenridge, hotly pursued by California authorities for undisclosed reasons. When the wife died, Pearl took the elderly man to Oklahoma and married him. When a national magazine writer came to Breckenridge to search out the story, the small town and the courthouse became the center of national media attention, bringing ordinary work in the building to a standstill.

Although continued oil production and sheep ranching helped stabilize the economy, the decades following the Great Depression continued to see a gradual decline in the county’s population, with figures falling from a high of 16,560 in 1930 to 12,356 in 1940 and 10,597 in 1950. Throughout these years, however, the Stephens County Courthouse continued to serve as the seat of county government and as a solid monument to the growth and prosperity of the 1920’s.

The most recent restoration work on the courthouse occurred in 1995 when the Mid-Continental Restoration Company performed $82,259 worth of work on the building. The outside was cleaned and re-mortared and some old iron work over the doors was recovered and put back in place. A flagpole atop the courthouse was also replaced after an estimated absence of 30 years. The interior retains most of its original elements, including the well-kept east courtroom. The west courtroom, however, has been divided into offices. Alterations to the exterior of the courthouse are extremely minor, consisting of the aluminum main entry door and windows and a handicap ramp added in 1985 to meet Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) specifications. Fortunately, these changes affect the overall historic appearance of the building very little, and county officials remain eager to keep the building historically accurate as well as functional.

The design and plan of the Stephens County Courthouse represents popular trends in courthouse architecture during the time of its construction. Its Classical Revival elements are commonly found in courthouses of the era. Of 254 extant courthouses in Texas, approximately 100 were constructed in various classical styles between 1900 and 1940. These larger buildings used classicism to provide an expression of dignity, reflecting ideals of civic pride and strength that courthouses were meant to represent. The building’s symmetry, Corinthian columns, and bracketing of the main section by end pavilions all identify the Stephens County Courthouse with this tradition.

Inscriptions and symbols carved into the stonework of the Stephens County Courthouse also reveal expressions of pride in local government and democracy, evoking associations with noble ideas. The inscription in the south frieze reads “JUSTICE, EQUITY AND PEACE ADMINISTERED ALIKE TO ALL PEOPLE.” In each capital is carved the likeness of an eagle below a lone star.

The classical elements of the Stephens County Courthouse are comparable to the Beaux-Arts Classic architecture seen in many federal buildings. While the Stephens County Courthouse might be commonplace in Washington, its design is significant if not unique in Texas for its combination of a Classical Revival design with the need for a larger public building.

David S. Castle of Abilene designed many public buildings in his career and while both the Stephens and Mitchell County Courthouses show classical influences, his later courthouses such as the Reagan and Sterling County Courthouses, built in the 1930’s, display Moderne characteristics. The Title, Luther, and Loving architectural partnership in Abilene houses Castle’s drawing collection; however, the only drawings found of the Stephens County Courthouse consist of some of the stone details. Floor plans could not be located during research for this nomination.

The Stephens County Courthouse presents a monumental facade to the nearby commercial buildings. Other contemporaneous buildings in Breckenridge are typically of a much smaller scale and consist of brick not stone construction. The use of stone in the Stephens County Courthouse represents a trend toward the return to the use of stone rather than bricks in public buildings to create a stronger image. The closest comparable building in Breckenridge is the 1922 Municipal building, also designed by Castle. This smaller, two-story brick building shows Classical influences such as columns flanking the main entryway. The Stephens County Courthouse retains a very high degree of its historic and architectural integrity-including the unusual retention of architectural elements from its predecessor building-making it the largest and most significant example of this type of architecture in Breckenridge and the county.